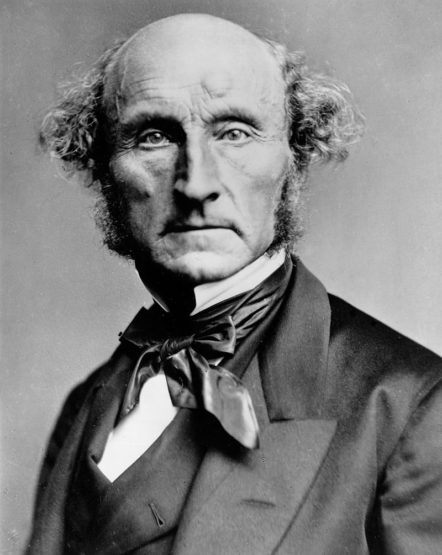

Explorer John Stuart – Chartered the overland telegraph line from Adelaide to Darwin.

Explorer John Stuart – Chartered the overland telegraph line from Adelaide to Darwin.

Posted on

Born and educated in Scotland, John McDouall Stuart (1815-1866) emigrated to Australia arriving in South Australia in 1839 at the peak of colonial exploration. The protégé of legendary explorer and South Australian Surveyor General, Charles Sturt, John McDouall Stuart began to make a name for himself as a capable bushman and reliable surveyor through a series of expeditions between 1858 and 1860 into the interior of the continent. These explorations were privately subsidized by wealthy graziers in search of suitable grazing areas and possible overland stock routes to Darwin.

Stuart’s success was a combination of his sharp navigational skills and an ethos that differed greatly from other colonial explorations. Stuart’s expeditions were small, accompanied by only two other men and a handful of horses, he followed watercourses and allowed the natural environment to determine his course. Where other expeditions set out to ‘conquer’ the land, Stuart worked with it and it was this vast respect for the arid and hostile nature of inland Australia that is attributed to his success.

Success that garnered the attention of Charles Todd, head of the Electric Telegraph Department of South Australia. In the years following the development of the telegraph as a primary means of communication internationally, the isolated colonies of Australia were desperately seeking ways of connecting themselves to the rest of the world and overcoming the months-long delays of written communication by ship. Todd envisioned an overland telegraph line from Adelaide, across the previously unmapped centre of the continent to Darwin, where a submarine cable could connect Australia to the international telegraph terminal at Java, Indonesia.

It was Todd’s political connections and lobbying that saw Stuart move from a privately financed surveyor to a government sponsored expedition leader. Building on the progress of his previous expeditions north of Adelaide, Stuart was charged with the responsibility of not only reaching the northern coast, but securing the resources necessary to build and maintain the vital telegraph line. Supplied with 10 men and £2500, Stuart once again left Adelaide on the 1st of January 1861 five months after another iconic overland expedition led by none other than Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills. The Victorian colony, thriving on the wealth of the Goldrush, had their own intentions for an overland telegraph and the two expeditions developed into a race that consumed the Australian colonies.

Ultimately, both expeditions would fail. But Stuart’s entire party returned alive after reaching as far north as Newcastle Waters, just 606km south of Darwin, further north than any European had yet reached, which was a feat in itself after the failure of the Burke and Wills trip. The sombre return reflected a changing public sentiment as excitement for exploration was dampened by its consequences on human life. To make matters worse, Stuart’s capacity for surviving the harsh Australian outback failed to extend back into social life. Though an accomplished bushman, Stuart’s strengths were incompatible with the realities of social life and his returns to civilization were marred by introverted descents into alcoholism: Stuart had an obvious predisposition to isolation. But the telegraph was still an essential piece of infrastructure for the colonies and Charles Todd immediately continued to lobby parliament for funding for another trip. On the 23rd of October 1861, just 5 weeks after his return, and still in ill health, Stuart left again.

The timing of this final expedition would cause extra strain. Walking north and into summer, the party faced the full severity of the Australian elements. Stuart records them in his diary:

“The country is a red light soil and covered with abundance of grass, but completely dried up. No rain seems to have fallen here for a length of time. We have not seen a bird, nor heard the chirrup of any to disturb the gloomy silence of the dark and dismal forest — thus plainly indicating the absence of water in and about this country.”

Retracing his steps of the previous expedition, Stuart again reached Newcastle Waters but pressed on. The party’s deterioration was exacerbated by the lack of water and Stuart himself contracted Sandy Blight rendering him almost blind. Nevertheless, on the 24th of July 1862 Stuart’s party reached the northern coast, to the great rejoice of both Stuart and his weary party.

“The Sea!” which so took them all by surprise, and they were so astonished, that he had to repeat the call before they fully understood what was meant. Then they immediately gave three long and hearty cheers. … I dipped my feet, and washed my face and hands in the sea.”

The momentous occasion, however, was inhibited by the party’s declining health and the 3000km return journey that still remained. Heading back towards Adelaide, the party lost several horses to dehydration and Stuart himself was carried on a stretcher, sure that he would die before the return to Adelaide.

“It was as much as I could do to sit in the saddle.”

And yet, on the 17th of December 1862, Stuart returned to Adelaide and to accolade, having secured the route for the overland telegraph that would be completed in 1872 and connect Australia to the rest of the world.